Desert Cultural Heritage

Sahara

The Sahara Desert is the largest hot desert in the world covering some 9 million sq. km (3.5 million sq. mi.) and extending across the whole African continent from east to west. No paved roads cross it from north to south. It separates the Atlas Mountains, Maghreb and Mediterranean coast to the north from the southern semi-arid grasslands of the Sahel and rest of Sub-Saharan Africa. The desert contains more than the massive dune fields, called ergs. It is divisible into discrete ecoregions including coastal, desert, steppe, woodland and montane areas.

Rainwater arrives mainly from the North African Monsoon, annual precipitation that varies in great cyclic patterns driven by orbital variation across millennia, that alternatingly expands and greens the desert as a lake-pocked savanna grassland. The most important of these cycles with regard to human cultural development was the last sustained wet cycle known as the African Humid Period, from about 14,500 to 4,500 years ago.

Ancient Cultures

The oldest stone tools (lithics) in the Sahara (Oldowan) date back nearly 2 million years to a time when hominins were first dispersing from Africa to Eurasia (Mutri, 2019). Later still simple tool industries (Acheulian) dating to about 1 million years ago are also present and equally rare. Around 150,000 years ago, a new toolkit called Aterian (Middle Stone Age) spread across northern Africa and Eurasia and was characterized by tanged (stemmed) arrowheads. This toolkit became rare around 80,000 years ago and disappeared altogether 20,000 years ago. Aterian stone tools were made by anatomically modern humans (Homo sapiens) who lived as hunter-gatherers across Africa 200,000 years ago. Their survival was threatened by the severe expansion of the Sahara to the margins of the Mediterranean from about 70,000 to 14,500 years ago.

Starting around 25,000 years ago during the Last Glacial Maximum, a distinctive stone tool industry of backed bladelets, the Iberomaurusian, appears along the northern coast of Africa. Named about a century ago after the Iberian peninsula and the former name for northern Africa, this tool industry is now believed to have emerged only along the northern coast of Africa during the glacial maximum. At that time, the Sahara had expanded northward toward the Mediterranean coast, with Iberomaurusian sites often preserved in limestone caves.

Chronologically, the Iberomaurusians lived at the close of the Pleistocene Epoch, which lasted from about 2.5 million years ago to 11,650 years before present (BP) and was followed by the Holocene Epoch (11,650 years ago to the Recent) and the recently-recognized Anthropocene Epoch (1945 to present), the latter defined by the prevalence of, and stratigraphic marker for, global human perturbation.

Kiffian and Tenerean Cultures

Starting around 14,500 years ago, with the advent of the African Humid Period, human occupation of the central Sahara greatly expanded. Wetter conditions prevailed across a “Green Sahara,” marked by tracts of vegetation, rivers and internally draining (endorheic) paleolakes. The origins of these ancient Saharans remains uncertain, as no one has been able to secure ancient DNA from the oldest Holocene burials in the Sahara. Ongoing research on the human skeletons at the Gobero site perhaps offers the best chance for direct evidence from ancient humans.

Kiffian. A distinctive hunter-gatherer toolkit emerged characterized by barbed bone harpoons, a more ancient invention that first appeared as early as 80,000 years ago in central Africa. By 10,000 ago, the ubiquity of barbed harpoons across the Sahara, from the Atlantic coast to the upper Nile valley, was recognized as the African “aqualithic” (Sutton, 1977). The harpoons and an associated stone toolkit, believed to include small embedded points (microliths), was called the Kiffian, originally named at the site Adrar Bous in Niger (Clark et al., 1973; Sereno et al., 2008). As harpoons, lithics and ceramics from the central Sahara are only recently being dated more precisely, new research will shed more light on the Kiffians, who typically buried their dead in supine hyperflexed postures without grave goods.

Tenerean. Around 8,200 years ago, a severe drying of the climate lasting a few centuries drove out all of the inhabitants of the Green Sahara. When wetter conditions returned, a new culture appeared in the center of the Sahara, the Tenerean (= “Tenerians”), also named at the site Adrar Bous in Niger (Clark et al., 1973). A wider array of stone tools were made, the most distinctive being the subcircular Tenerean disk. This particular artifact, made only of felsite from quarries in the Aïr highlands and known only from southern Algeria and northern Niger, is the first sign of cultural diversification within the Sahara. Their stone toolkit included spear points, arrowheads, ground stone tools and barbed bone harpoons and hooks (Sereno et al., 2008). The Tenereans came to bury their dead in less flexed side postures, often including grave goods (ceramics, ornaments, animal bones and teeth) for an afterlife.

Rock art. Rock art is abundant in many areas of northcentral Niger- in and around the Aïr highlands, in the Ténéré Desert around Fachi, and in the far northeast at Djado Plateau. Discovered in 1987 on the western flank of the Aïr north of Agadez, the 20-foot tall DaBous giraffes comprise Niger’s most famous, well-documented example, a deeply-incised naturalistic rendering of male and female giraffes and their distinctive coloration with leashes extending from their muzzles. There are nearly 1,000 additional rock engravings in the surrounding rocky outcrops, carved or scratched through the dark surface patina typical of many rocks exposed to the harsh sand and wind of the Sahara.

The DaBous giraffes are now widely regarded as having been completed by Kiffian peoples around 8,000 years ago, whereas scratch depictions of people and animals with characteristic hairstyles, spears and handbags are regarded as Tenerean in age, drawn some 4,000 to 5,000 years ago, the most famous of which from the western edge of the Aïr at Anakom and Arakou. Depictions of camels are younger still, as we have a good evidence for the arrival of dromedary camels from the Near East some 2,000 years ago. Saharan rock art, now receiving the attention it long deserved for needed conservation efforts (TARA), provides a rich and unique cultural record starting in abundance as far back as 12,000 years ago.

Today’s Genetic Geography

The most recent surveys of genetic signatures from indigenous human populations across northern and central Africa suggest a shared genealogy (Y-chromosome haplogroups) dating back to the Green Sahara when populations mixed with considerable gene flow (D’Atanasio, et al., 2018). Later major human migrations into northern Africa with recognized genetic traits include the Berbers of Near East origin and the more recent descendants of the Muslim conquest of the Maghreb (~640-740 AD). Berberism, a political-cultural movement taking root in places in northern Africa, recognizes their distinctive origin and opposes a pan-Arabist political and cultural viewpoint.

Today’s Desert Peoples

Today, an array of nomadic, semi-nomadic and settled peoples live in the Sahara. Some trace their roots to a language family, Nilo-Saharan, thought to have a common origin several thousand years ago. Among them are Songhai-, Zarma- and possibly the Tebu-speaking peoples in Niger, Chad and Libya. Fula-speaking peoples are also present, their language tracing to a different family across the middle of the continent, the Niger-Congo. And finally, the Tamasheq-speaking Tuaregs, a Berber language, pertains to the Afroasiatic (Semitic) language group found across northern Africa and the Near East.

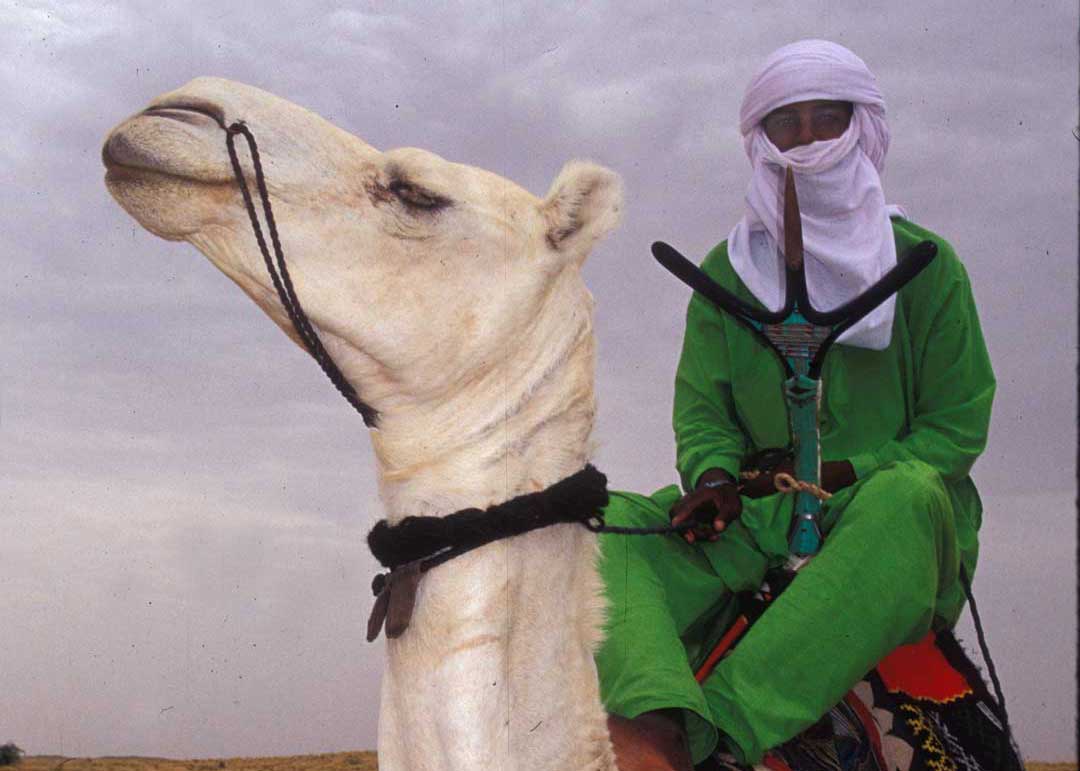

Tuaregs, the veiled “blue people” of the Sahara, speak several dialects of Tamasheq and use an ancient vowel-less script called Tifinagh. The Tuareg population of around 2 million people is spread across a large area of the middle and western Sahara as well as the Sahel. They are traders and nomads practicing transhumance, or the seasonal movement of people and livestock between fixed summer and winter pastures. Livestock include dromedary camels, Zebu cattle, donkeys, sheep and goats.

Fulani (Fula) are widely dispersed Fula-speaking people numbering as many as 40 million worldwide that include an estimated population of 12 to 13 million in Niger. As pastoralists of long-horned cattle, the Fulani represent the largest nomadic pastoral community in the world. The Fulani include the Wodaabe, a small subgroup (numbering several hundred thousand) of cattle-herders and traders located predominantly in the Sahel of Niger.

The Tebu (Toubou) are a nomadic and semi-nomadic people with a population of around 2 million living in small communities dispersed across northeastern Niger and around the Tibesti Mountains in Chad and southern Libya. Tebu tend to livestock and date harvesting in scattered oases, herding dromedary camels, Zebu cattle, donkeys, sheep and goats.

Today’s Desert Culture

Despite the pressures of advancing desertification, periodic rebellions, incursions by bandits and armed subversives, a flood of West African migrants, and the influences of globalization, culture in the Sahara Desert continues to thrive in traditional, adapted and new forms of handcrafts, jewelry, textiles and clothing fashions, dance and performance art, music and poetry.

Some traditions and artists have achieved global notoriety. The former include “Tuareg crosses,” pendants (teneghalt) of 21 styles tied to geographic locations that are made of silver by artisans (inadan) using the lost wax process (Loughran and Seligman, 2006). The latter include Alphadi, an award-winning fashion designer with boutiques in Niger, Paris and elsewhere who created the celebrated biannual fashion festival FIMA launched in Niger, and Bombino, a celebrated guitarist and songwriter, recording artist and Grammy nominee whose songs in Tamasheq capture the spirit of resistance and rebellion, a mesmerizing brand of “desert blues.”

Desert culture in Niger thrives in many modes and forms, the summary below highlighting select examples prominent in and around Agadez, an oasis town, that as recently as 1975 had fewer than 10,000 residents, and surrounding areas. Today Agadez has grown to a population of at least 125,000, transforming what was once an intimate nomad-dominated crossroads of the Sahara into a sprawling mélange of cultural influences. The “Hausazation” of Agadez, as some refer to the contemporary scene, involves the arrival of considerable numbers of West African traders and migrants as well as Islamic fundamentalists.

What will happen to traditional desert cultural expression with its inevitable integration into an increasingly global cultural commodification (Seligman, 2006; Schmidt, 2018)? NigerHeritage aims to create a museum center in Agadez that celebrates the ancient past, preserves and teaches desert cultural traditions, and provides a space for the creative handwork, sounds and words of future generations.

Handcrafts. Handcrafts in leather, metal, wood, clay, and basketry have been developed over millennia in the Agadez region and include leather bags, saddles, sandals, swords and daggers, ceramics, woven baskets as well as furniture and musical instruments. Tuareg artisans often make objects of everyday life, guided by aesthetic beauty and functionality unrelated to religion or ethereal spirits (Ewangaye, 2006).

Jewelry. Earrings, necklaces, bracelets, rings and anklets in silver comprise a rich and historic tradition in Tuareg culture. Other metals, several kinds of stone from the Aïr, beads in red and black, and leather are also utilized in jewelry. Simplicity in form and decorative motif characterizes the jewelry of Saharan desert cultures, which is worn by both women and men (Loughran, 2006).

Textiles and clothing. Niger’s desert cultures are characterized by distinctive textiles, garments and clothing accessories, including handwoven tapestries, hand-dyed indigo and batik fabrics, and embroidered traditional textile products. Traditional Fulani hats are made from handwoven plant fibers and decorative leather strips. As Nigerien fashion designer Alphadi remarked, “fashion is about more than clothing —it’s often a form of identity, dignity, a way to be heard, recognized and respected.”

Dance and performance art. Desert festivals, some traditional and some more recently established, involve different forms of dancing and performance art. The Festival of the Aïr showcases traditional dances performed by all 15 communities composing the Agadez region. Another well-known large scale festival, Cure Salée, is a celebratory social gathering and courtship ceremony marking the end of the rainy season. As part of the courtship ritual, Woodabe men perform the grueling Guérewol, a group dance and chant that may extend over days as proof of stamina and attractiveness.

Music. Traditional instruments of the Agadez region include a skin-covered drum, the tindé, and a one-stringed fiddle, the imzad, both played traditionally by women. Younger generations from widespread regions of the Sahara and especially Niger have taken up electric guitar to create styles such as “desert blues” and others, featuring songs in Tamasheq that often addresses nomad identity and rebellion. Artists and bands gaining worldwide recognition include Toumast, Mdou Moctar, Bombino, Etran Finatawa and Tinariwen.

Literature and poetry. Mano Dyak, celebrated Tuareg activist, negotiator and author, penned a landmark book in 1992, Touareg, la Tragedie, in which he spoke of the rich Tuareg culture (tamoust) that nurtured his youth in the Aïr highlands and his fight to safeguard its future, as well as achieve for nomadic peoples of the north a measure of economic justice, education, health care and self-government.

For Tuaregs, poetry stands as a powerfully expressive tradition. Well-known poet and author, Hawad (Mahmoudan Hawad), like Mano, was born in the Aïr highlands. He writes in Tamasheq and French about the thirst, hunger and episodic movement of nomadic desert life as well as themes connected to political resistance and social freedom from oppression. For Saharan nomads including those in Niger, the last century of colonial and postcolonial rule has been a story of survival in spite of a series of natural and manmade calamities.

Sahara parched-green cycle

Sahara parched-green cycle

Sahel and Sahara monsoon cycles

Sahel and Sahara monsoon cycles

African wind and rainfall patterns

African wind and rainfall patterns

Saharan Ubari Oasis in Libya

Saharan Ubari Oasis in Libya

Aterian arrowhead

Aterian arrowhead

Kiffian posed burial

Kiffian posed burial

Tenerean disk

Tenerean disk

Rock art of DaBous giraffes

Rock art of DaBous giraffes

Rock art of a herd of giraffes

Rock art of a herd of giraffes

Rock art of a pair of giraffes

Rock art of a pair of giraffes

Rock art of camel

Rock art of camel

Tuareg men

Tuareg men

Tuareg man

Tuareg man

Fulani men

Fulani men

Gerewol festival

Gerewol festival

Toubou man

Toubou man

Toubou woman

Toubou woman

Agadez cross

Agadez cross

Tuareg leatherwork

Tuareg leatherwork

Tuareg dagger

Tuareg dagger

Artisan blacksmith

Artisan blacksmith

Leather saddlebag

Leather saddlebag

Fulani hat

Fulani hat

Gerewol festival

Gerewol festival

Cure Saleé festival

Cure Saleé festival

Bombino

Bombino

Mano Dayak.

Mano Dayak.

Mahmoudan Hawad.

Mahmoudan Hawad.